Diversity, Equity & Inclusion in the US Military

-

In the 1990’s the US military stopped short of a full revolution in lifting restrictions on military service for women and members of the LGBTQ+ community, instead instituting half measures. It allowed women access to combat roles on airplanes and battleships while keeping restrictions in place prohibiting women from fighting in ground combat. It rolled back the blanket prohibition on “homosexuals” in the military, replacing it instead with a policy known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT). On the surface DADT was more permissive, but in reality it increased the rate of dismissals based on sexual orientation.

Less than a decade later these policies came under increased scrutiny as the US military fought protracted counterinsurgencies in Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2011 the US military instituted the repeal of DADT, and five years later opened all combat roles to women. In 2020 the Department of Defense lifted restrictions on transgender service members.

With formal restrictions a matter of history, women and the LGBTQ+ population face a landscape similar to that of populations of color. The US military officially banned discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion and national origin in 1948. Seven-plus decades later, though, the up-or-out competitive nature of active duty military service, combined with accession practices that amplify pre-existing privilege, have excluded people of color from many of the most prestigious roles. For instance, although some 43 percent of the 1.3 million men and women on active duty in the United States military are people of color, in the Air Force, where pilots typically hold the highest status positions, only 1.7 percent of pilots are African–American or black.Description text goes here

Women in Combat

Often cast as a “battle of the sexes,” the debate over women in combat is dominated by questions of physical standards, push-ups and pull-ups and deadlifts and sprints. However, the transformation underway is about much more than the status of women. It is about how an institution built on the ability to conform approaches diversity in all its variations. How does the uniformity of the US military incorporate difference? Does opening the most prestigious combat roles to women change the military? Or does it change the women?

This project addresses these questions through the eyes of the self-described ‘Gunship Girls,’ the first women to hold combat roles in Special Operations Command. The Gunship Girls flew the deadliest missions of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as members of AC-130 Gunship crews. However, unlike the high profile fights over the integration of military academies, and the fighter community, the integration of women into Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) largely unnoticed. This project tells their previously untold stories.

Publications

Nuclear Strategy and Politics

The Symbolic Power of Nuclear Weapons: The Case of Iran

Despite widespread recognition that nuclear weapons have value as a symbol of power and prestige, we know relatively little about the source and utility of that value. Existing literature explores symbolic status as a motive for nuclear proliferation but has less to say about whether or how states capitalize on that value. What determines the socio-political utility of nuclear weapons? Which strategies have states used to leverage their symbolic value? And to what ends? This article project addresses these questions by developing a theory of nuclear value and illustrating the utility of that theory by applying it to the case of Iran. The overarching claim it makes is that nuclear weapons have evolved into a distinctive socio-political object; in addition to being a weapon of war, nuclear weapons have also become a ‘power commodity.’ Their possession has long brought states either infamy or prestige, but increasingly states have begun viewing their value pragmatically, seeking to ‘trade’ on their possession to secure a range of political, economic, and military outcomes.

Behavioral Economics and Nuclear Weapons

Will cognitive science and behavioral economics put the last nail in the coffin of homo atomicus? The assumption of the rational, utility-maximizing actor has done a lot of work for nuclear deterrence theory. Rational choice is a seductive form of logic for any social system that entails a combination of conflict and cooperation. And there is nothing that epitomizes this tension like the dynamics of nuclear deterrence and nonproliferation. The assumption of a rational actor is at the center of nuclear deterrence theory and nonproliferation policy and the incorporation of systematic deviations from that idea into theory holds out the potential of being paradigm shifting on a tectonic scale. In this project we explore whether insights from behavioral economics about how actors often behave in predictably irrational ways will change the way we think about nuclear deterrence.

Publications

Highly Nriched

Our first-of-its-kind, nonprofit, non-partisan online platform creates a synergistic experience for educators in the nuclear field by combining teaching resources with a broad-based mentor network of policy practitioners and experts.

Highly NRiched is a first-of-its-kind, crowdsourced platform for teaching and mentoring resources on nuclear issues. It promotes diversity by breaking down barriers to sharing and accessing resources. Its synergistic experience combines educational resources with a broad-based mentor network of policy practitioners and experts.

The idea for Highly NRiched came out of a year-long design process supported by NSquare and the Rhode Island Institute of Design. The inspiration for this project is the documented need to support and promote education on technically and socially complex topics like weapons of mass destruction in order to raise awareness of their dangers. NRiched incentivizes educators to incorporate lessons about WMD into their classrooms by making it easy for educators to share, access, and build curricula.

Highly NRiched’s tech-based solution takes advantage of the transformation underway in how educators provide resources to students. It provides educators with teaching and mentoring resources in one easily searchable, online hub. Educators can search a database of crowdsourced games, simulations, videos, and podcasts to build bespoke curricula that are easily uploadable onto courseware sites.

Highly NRiched’s mentor network bridges the gap between academia and the policy community. The site is supported by a community of more than one-hundred policy makers and nongovernmental organization experts who have volunteered their time as guest speakers and/or professional mentors and can be contacted through Highly NRiched’s mentor portal. Together these elements create a synergistic user experience. Experiential learning exercises engage and motivate students and a vibrant expert mentor network facilitates engagement with the community.

Teaching

-

The outbreak, course and consequences of war have and continue to profoundly shape political, cultural, social and economic practice both internationally and within different states and societies. In this module, you will be encouraged to consider war as a lived human experience rather than as a clearly bounded or exceptional phenomenon. You will examine and debate how war and military force, whether interstate, extra state or intrastate in form, shapes and is shaped by different societies, communities and individuals. The module will ask how war is made possible in and through everyday situations and practices as well as geopolitical ones. It will examine how war and violence make, permeate and alter societal institutions, economic practices, language and cultural expression and it will explore the impact and legacies of war for societies, communities and individuals through a series of issues.

The lectures are organized into four parts. The first situates the approach to war as a lived experience within the disciplinary contexts of international relations and sociology. The next three parts address the experience of war by considering issues at the nexus of war and society in terms of different forms of war, and/or its actors. The arc of the module is thematic; we begin the module by theorizing the relationship between war and society, and follow on with different kinds of wars and conflicts that marked the period between World War II and today. Finally, we conclude our module by asking what happens when war ends, what it means to “win,” and exploring questions around post-conflict reconstruction and memorialization.

-

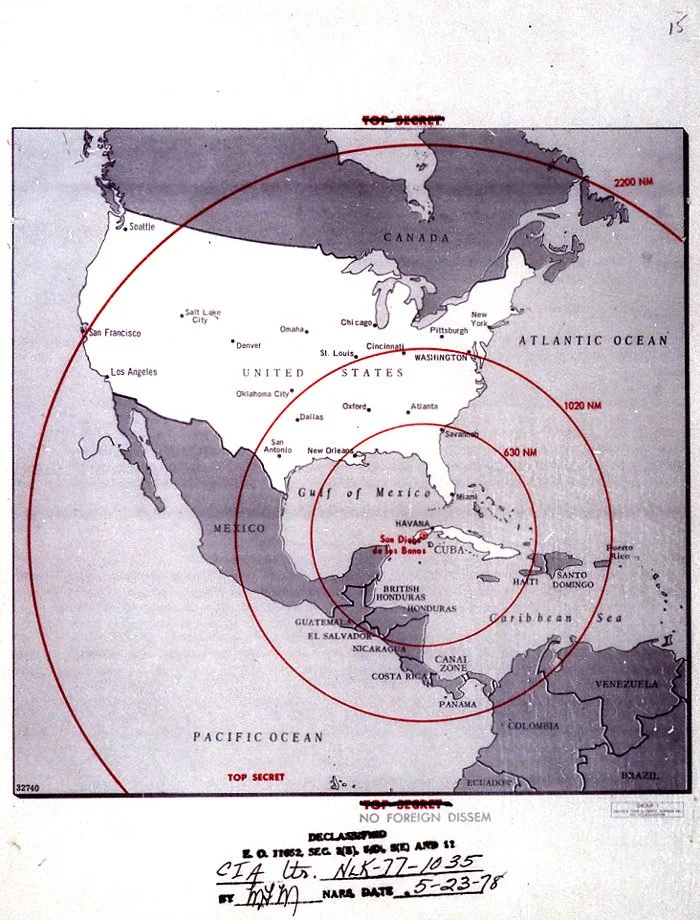

This course aims to provide you with an interdisciplinary understanding of international nuclear politics from the advent of the atomic bomb project in 1941 to the present day. The first part of the course will be devoted to an episodic study of the history of nuclear politics during the Cold War, with the aim of showing how the danger of atomic and nuclear war decisively shaped the conflict between the US and the USSR—and how it determined its ending. The second part introduces the problem of dual-use and the challenges of nuclear proliferation. It includes a Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty simulation exercise. The third part explores contemporary problems and modes of analysis: of the key features of nuclear power politics today and major theoretical attempts to understand them. The fourth part provides an overview of five attempts to solve the nuclear dilemma.

-

As technology enhances and expands human capabilities, the conditions of political and technological possibility become increasingly interlaced. From advances in weapons and surveillance systems to the collection and analysis of big data, political decisions are technologically complex. Political decisions are so conditioned by the existence of technological systems, which are themselves the product of prior political decisions, that speaking of them as discrete occludes the primary challenge of political life today, which is precisely to understand the implications of what it means for politics and technology to be inscribed in one another.

This module takes its title from the work of Gabriele Hecht, who speaks of “technopolitics”: a term she uses to denote the many processes by which technological systems come to be appropriated for political ends or serve as a vehicle through which politics unfolds. The term is useful as a way of drawing attention to the complex dynamics wherein political choices shape technologies, which subsequently shape socio-political outcomes. Arguably, when conceived of in this way, the very idea of a ‘political decision’ as a singular act that can be conceived of as separate from technological processes becomes problematic.

Taking the notion of technopolitics as a starting point, the course will introduce you to mid- twentieth century debates about transformational technologies, such as nuclear weapons, as well contemporary frameworks for understanding the complex interconnections between science, technology and politics. You will be asked to address questions such as: How we should conceive of the role of technology in political life? Does technology have agency of its own? What is the appropriate role of scientific experts in within political processes?

-

The central focus of this module will be on the ways gender, race and sex matter in global politics. The range of topics studied will include a selection from: militarization, popular culture, the global political economy, the politics of memorialization, the beauty industry, postcolonialism, tourism, black feminisms, nuclear weapons, masculinities, the Women, Peace and Security agenda, the war on terror, and the gendered and raced character of ‘death’ (which dead bodies matter? Which dead bodies ‘count’ and/or are counted?) Central questions underpinning this module are: where are the women in global politics? What work are masculinity and femininity doing? What work is sexuality doing? How does race matter? How and why does gender matter in the high political realm of international/global politics? Where do we ‘see’ gender in global politics? Which gender(s) do we see? Students will be introduced to some of the central concepts in feminist theory, gender theory, masculinity studies, critical race theory and theories of coloniality which will be used to examine key issues in global politics (some of the ‘issues’ may not be ‘obvious’). Texts studied will include conventional texts as well as films, videos, social media/blogs, news reports, art, cartoons etc.